Too Hot to Handle: How Improper Storage and Shipping Can Ruin Your Wine

... and why you should stop your friends from storing wine in the kitchen.

That wine is a rather fragile beverage is possibly one of the most frustrating lessons which most of us interested in wine will have learnt the hard way at some point in time. I remember a wonderful trip to Italy's Valpolicella region, where after enjoying a lovely tasting and buying a bottle from a small boutique producer of Amarone, we stopped by the shores of the beautiful Lake Garda for a spot of lunch. The bottle remained tucked nicely out of sight in the rear footwell of the little Fiat 500 I had rented, and with partial shade covering the car I thought no more of it.

Of course, though we had only been gone for around 30 minutes, the car was absolutely sweltering when we returned and had, predictably enough, completely cooked the wine, leaving a jammy, unpleasant shadow of what was a beautiful drink mere moments ago. The financial hit was marginal, but that moment has stuck with me ever since as a prime example of just what temperature can do to a wine.

The thing is, however, it needn't always be quite as extreme as that. You will more than likely enough have visited someone's house in which they store their wines on a kitchen shelf or in the living room. While quite possibly fine for a brief moment, any long-term storage under such conditions can just as easily strip a wine of its character, leaving the wine irreparably damaged, flabby, tasteless and without any vibrancy it may have had on leaving the winery.

It can be a deceptively difficult thing to identify as well. Unless taken to the extreme, as with the sad case of my bottle of Amarone, a poorly kept wine may just appear, particularly to the untrained palate, as just a low-quality wine. Without another bottle of the same wine to compare it to, ideally one directly from the cellars of the winery in question, the blame for the perceived low quality of the wine is often shifted onto the winery as opposed to the careless handling of supermarkets, delivery services and more often than not the consumer themselves.

In Greece last year, I picked up a bottle in a supermarket from a producer I was due to visit the next day, just to get a feeling for what to expect. While OK, it was rather disappointing, with harsh undertones that I associate with lower-end bulk wine, and had it not been for the fact that the producer was a friend of the family I would have probably insisted we make alternate arrangements. Happily, however, the very same bottle and vintage, when served at the winery, was delightful! It was full of fresh fruit and lively acidity that left you wanting more. Not at all like its supermarket sibling, which had been reduced to mere plonk. Aside from highlighting the fact that the best expression of any wine will always be the one you get at the winery, it shows just how important temperature control, among other variables like light, is for the quality and longevity of the wine.

So what actually causes this sensitivity to temperature, and what happens to the wine? How should wine be stored to avoid damage, and is there anything you can do to prevent buying a damaged bottle? Does the style of wine, SO₂ levels and closure type matter? These are the questions I'm hoping to get some further clarity on in what follows.

Some Chemistry

A 2021 study titled Wine Storage at Cellar vs. Room Conditions: Changes in the Aroma Composition of Riesling Wine by Tarasov et al. delves into just this issue, looking at how different storage temperatures influence the evolution of a wine’s aromatic profile over time. Focusing on Riesling, a varietal well known for its vibrant fruity and floral aromas, the researchers stored identical bottles at two temperatures—12°C, representing traditional cellar conditions, and 20°C, a common household storage temperature—and monitored their chemical composition over 12 months using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). This method allowed them to track the presence and degradation of volatile compounds responsible for aroma, revealing significant differences between the two storage environments.

At a molecular level, temperature directly affects the rate of chemical reactions, and the reactions happening in wine are not exempt from this dynamic. Warmer conditions accelerate processes such as ester hydrolysis, oxidation, and Maillard reactions (a non-enzymatic browning reaction that occurs between amino acids and reducing sugars during cooking, responsible, among other things, for the brown crust on bread and the flavour of seared meat), all of which contribute to changes in aroma and flavour. Esters, which are responsible for fruity and floral notes in young wines, are particularly vulnerable to breakdown at higher temperatures. These compounds form when acids react with alcohols, but they are not stable over time—especially in warmer conditions. As the study found, wines stored at 20°C experienced a more rapid degradation of esters, leading to a noticeable decline in fresh, fruity aromas. This explains why improperly stored Riesling can lose its characteristic bright citrus and stone fruit notes, making it seem duller or flatter in comparison to its well-preserved counterparts.

Simultaneously, higher temperatures promote the accelerated formation of compounds associated with ageing. One of the most well-known of these is TDN (1,1,6-trimethyl-1,2-dihydronaphthalene), which gives mature Rieslings their distinct kerosene or petrol-like aroma. TDN formation is influenced by multiple factors, including grape composition and winemaking techniques, but temperature plays a key role in how quickly it develops. At 12°C, this transformation occurs gradually, allowing the wine’s aromatic complexity to evolve harmoniously. However, at 20°C, the production of TDN and other ageing-related compounds is sped up, causing the wine to take on aged characteristics prematurely. While some level of TDN development is desirable in Riesling, excessive early formation can overwhelm the wine’s more delicate notes, leading to an imbalance.

Oxidation is another crucial factor affected by temperature. Although wine bottles are sealed to limit oxygen exposure, minute amounts still interact with the wine over time. Higher temperatures increase the rate at which oxidative reactions occur, leading to the breakdown of fruit esters and the formation of aldehydes, which can impart stale, nutty, or even sherry-like aromas. This effect is particularly problematic for wines like Riesling, where freshness is a key part of their appeal. Furthermore, oxidation contributes to colour changes, with white wines developing a deeper golden hue more quickly when stored at room temperature compared to cellar conditions.

All in all, this study does a good job of reinforcing the importance of proper wine storage, particularly for varietals like Riesling that rely on a delicate balance of aromatic compounds. That is of course a broad range of wines, as so many of the best wines out there rely on delicacy and complexity. In short, the science is clear: heat accelerates chemical reactions, pushing a wine towards premature ageing and altering its intended sensory profile. For collectors and wine enthusiasts looking to preserve the freshness and complexity of their wines, a stable, cool storage environment—ideally around 12°C—is essential.

So while there is clear empirical evidence to support the long-standing belief that cellar storage is key to maintaining wine quality and graceful ageing, it is well worth noting that the controlled conditions under which this study was conducted are a far cry from the microclimates that can be created in a living space. A living room can get sweltering in the summer sun, with temperatures well exceeding 20 degrees, even in the shade. Even worse, of course, is a kitchen environment, where temperatures can swing dramatically as meals are cooked, with wines often placed high up on a shelf or on a cupboard, where the temperature would be even higher than the ambient.

The Role of SO2 and Tannins

There is of course more to it than just temperature. The composition of the wine in question will have a great impact on its ability to not only age well in general, but to withstand more challenging storage environments for longer. Sulphur dioxide (SO₂) and tannins (in the context of red wines) play central, complementary roles in protecting wine from the damaging effects of heat and improper storage. SO₂, ignoring for a moment the range of misunderstandings associated with sulphites among many consumers, acts primarily as an antioxidant and antimicrobial agent. While all wines contain some SO₂ created by yeasts, winemakers will more often than not supplement with sulphites so as to ensure the microbial stability of the wine and prevent spoilage.

In properly stored wine, SO₂ scavenges oxygen and neutralises hydrogen peroxide, preventing oxidative reactions that would otherwise degrade colour, aroma, and flavour. However, at elevated temperatures, the rate of oxidative reactions outpaces SO₂’s protective capacity. Not only is SO₂ consumed more rapidly, but its molecular form (the most active form in wine) decreases as temperature rises, making it less effective. Once depleted, the wine becomes highly vulnerable to oxidation, allowing compounds like ethanol and polyphenols to react with oxygen and form aldehydes, brown pigments, and off-aromas.

Tannins, on the other hand, provide a structural backbone in red wines and also contribute to oxidation resistance through their ability to bind with oxygen and reactive species. Under normal conditions, they polymerise slowly over time, contributing to the graceful ageing of wine. But when exposed to heat, tannin polymerisation is accelerated unnaturally, often leading to the formation of large, insoluble compounds that precipitate out. This not only strips the wine of structural balance and mouthfeel but also reduces the pool of phenolics available to buffer oxidation. Moreover, oxidised tannins themselves can contribute to bitterness and astringency. In this way, SO₂ and tannins can be seen as the wine’s built-in defences—chemical armour that begins to break down under thermal stress, setting off a cascade of degradation that affects both the chemistry and the sensory integrity of the wine.

It should come as no surprise then that natural white wines, often with no added sulphites as a matter of principle and no or minimal tannins, are rather susceptible to improper storage. Though not a main focus of this article, it is also worth noting that many of these wines are also bottled in clear glass bottles to accentuate their fresh, natural and easy-going character to the consumer. This dramatically increases their susceptibility to light strike, which, though a different process than heat damage, can also strip a wine of its character. The cumulative effect of both—imagine a clear bottle in a bright, room-temperature environment—is catastrophic for the wine. For an in-depth look at light strike, check out my article on clear glass usage for rosé wines.

The Role of Closures

Cork—natural, sustainable, and malleable enough to contain the wine in the bottle—has been the preferred choice for wine closure since the 1400s, and it is only quite recently that the role of alternative closure mechanisms warranted much discussion. The main alternative to the natural cork is, of course, the by now well-known screw cap. Lauded for its ease of use, ability to maintain freshness in wines, consistency of quality, and relative cost-effectiveness, they have done a fantastic job of upsetting the sensibilities of the traditionalist. Yet for their lack of aesthetic flair, screw caps do a good job of keeping the wine in the bottle, and with clever liners, allow the same level of oxygen exchange between the wine and the outside world as a traditional cork.

So that begs the question: does the type of closure impact the wine’s ability to withstand elevated temperatures? In short, no. The chemical reactions described at work will still speed up and ruin your wine should its temperature get too high for a long enough period. That said, it’s a bit more complicated than that. As highlighted by this 2019 article in Decanter, when a wine is exposed to excessive temperatures, the wine and air inside the bottle expand, pushing the cork out partially, which can lead to leaks and, conversely, ingress of oxygen. When, on the other hand, the wine experiences a rapid cooling, the pressure inside the bottle drops below the ambient pressure, a slight vacuum is formed, which can also lead to excessive oxygen ingress. The article I link to above isn’t the most scientifically robust, but that there is a mechanical aspect to how corks respond to the varying pressures they experience at different temperatures holds true.

Being made of metal, the screw cap will not budge, however, which means that there is less risk of the seal being compromised. This has its downsides as well, however. While the elevated temperatures required to mute, alter, or ruin the expression of a wine needn’t be that extreme, a cork that has been partially pushed out, bulging the foil, is one of the surest signs that the bottle has been through rough times. It is also one of the few indicators available to the consumer, who more often than not will be unaware of the travel history of any given bottle. A screw cap bottle will show no outward signs of having been ruined, even when it’s been through the full back seat of a Fiat in Italy experience. That said, a conventional cork may well also not betray any trouble, so it’s far from a guarantee.

How to Avoid Buying a Damaged Bottle?

The surest way to ensure you get what you’re paying for will always be to buy directly from the winery. Not only does this benefit the producer greatly as they bypass the usual three-tier system, but you can rest assured that the only travel the wine has done is from the barrel room to the bottling station and into the temperature-controlled cellar. That is, however, not always an option, and it will often come down to how well the retailer, and those involved at every stage in between them and the winery, understand the perils of elevated temperatures. Purchasing from a reputable establishment is therefore usually the best way to go, but even at the high end that is not necessarily a guarantee, as wines acquired from private cellars, though often in excellent condition, may well have had a more troubled past. There’s really no way to know unless you taste the wine.

With regard to wine that is delivered, however, there are some general rules that can be followed, and which conscientious wineries will enforce towards their wine club members. First and foremost is only shipping and delivering wines during a time of year that is not prone to excessive temperatures. No matter how well you store your wines, there is no repairing the damage that 30 minutes in the Texan sun, or in the back of a sweltering UPS truck, will do to your cherished tipple.

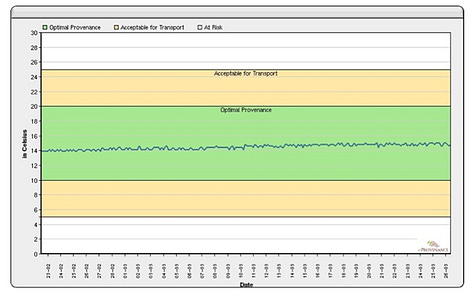

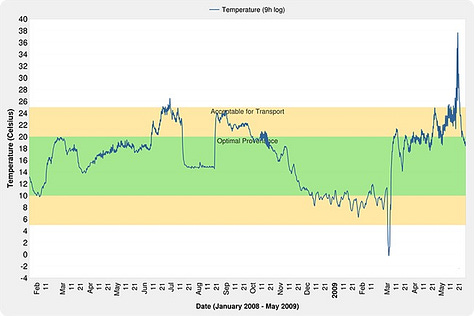

The better wineries out there, recognising the potential reputational damage a spoiled delivery can create, utilise in-case temperature trackers. This technology has been around for a long time at this stage, and there is really no excuse—particularly for finer wines—not to employ it. Aside from ensuring that nothing untoward happens to the bottle, it allows wineries to claim against insurance should the temperature of the wine pass certain thresholds deemed to be detrimental to its quality. Quality producers like Burgundy’s Domain Ponsot have been employing this technology since 2013 for instance.

Final Thoughts

Temperature is undoubtedly one of the main factors that affects the quality of the wine we drink, and knowing just how quickly a wine can lose what makes it great has made me rather particular about storage. Living in a London flat—which, unsurprisingly, doesn’t come equipped with deep, cool cellars that stay at a constant temperature year-round—I rely on a wine fridge. In all honesty, it’s the best solution for most of us. Some are extremely fancy, with wooden drawers and dual zones for whites and reds, but even a modest model will do the trick. That said, they’re not cheap, they take up space, and they might not seem worth it for the average consumer (though I suspect that if you’ve made it this far, you’re more than a little into wine).

Most people, of course, have a regular fridge, which typically keeps things at around 4–7°C, depending on your settings. The only real difference is that a wine fridge maintains a steady 12–13°C—too warm for food, but ideal for wine. Where higher temperatures accelerate chemical reactions, lower ones slow them down, making your everyday fridge a decent, if not perfect, alternative. If you don’t want to dedicate fridge space to your wine, a dark cupboard or closet away from radiators, ovens, or direct sunlight can be fine for short-term storage. But generally speaking, most living spaces are too warm and variable for storing wine long-term.

If you find yourself picking up a few bottles on an Italian road trip, however, your options may be even more limited. The best tip I can offer? Take the wine with you when you leave the car and keep it in the shade. If you buy more than is practical to lug around, arranging for a shipment home may be your safest bet.

Would love to hear your thoughts on this—especially if you’ve got any horror stories about cooked wine. Until next time, take care, and drink something good!

LOVE this topic. I have to say, I think a lot of bad bottles are in all wine shops across my country as shipping is long, hot and so many factors occur. I can first hand say, in the market where I was a wine distributor sales rep- our company had a 4hr drive from warehouse to market drop offs and NO AIR CONDITIONER in the van they transported wines to and from in. This was the Southeastern resort areas of the United States where in the summer temperatures were over 95 degrees and humidity over 70%. I know first hand half those bottles were destroyed and yet people bought them, drank them none the wiser. But they probably never purchased that wine again. And this was a portfolio of stunning European wines.

Sometimes just waiting to clear customs in America can take hours and only the big distributors or ones with deep pockets have refrigerated vans and trucks. It is rather awful really, especially when sometimes they have well over 10+ hours to drive to the warehouse to store the wines. I honestly wish this was talked about more, so thank you!!

I spend an enormous amount of money on offsite storage every year. That said, let me see if you can answer a question no other wine professional or non-professional has been able to answer when I bring it up.

2003 was an incredibly hot summer in Europe. At that time, few European wine warehouses were temperature-controlled. Even if they were underground (and many/most weren't), temperatures got very warm for very long periods. Yet we see no overall ill effects in the wines from 2001 and 2002 that sat in those warehouses.